The few, the proud, the optimizers. I’m one of them, as are my closest friends. Birds of a feather do indeed flock together. The distance we’d go to seek out that last 1% increase is remarkable, but more importantly, questionably worth it. It’s just too tempting to avoid until you look back on parts of your life where you could’ve been further ahead had you not wasted time searching elsewhere. There is, however, a difference between leaving and returning versus never having left at all (or at least I heard that somewhere and it sounded smart).

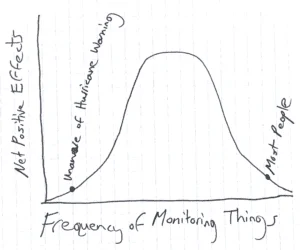

The first person to nail this concept home for me was Tai Lopez of all people (ask me about my checkered past with him one day. To his credit he spoke with me for 45 minutes just because I asked for it, where he informed me of the “40/70” rule and how to apply to decision making. If you have roughly 40% of the information available, continue seeking more information until you get closer to 70%. Once you attain 70% of the information to be had, make the decision! The temptation for optimizers like myself is to push past 70%, but the marginal returns of more information sharply decrease as your opportunity costs of doing so rise. Put in plain English without me overly forcing in my Economics degree verbiage (forgive me, I’m still trying to prove out my college ROI), it’s often a waste of time to find the ever so slight improvement.

If instead you use that time you would spend searching on exploiting your existing opportunities you’ll probably get farther ahead ultimately. I’m jealous of simpletons who can put their heads down and work on what’s right in front of them. I’m too busy dreaming about what else is out there and what else is possible. As is the answer with basically everything, there’s a balance to be had. The world has done a lot of this thinking and number crunching for you, and it’s called basic economics; if something is that much better, the supply and demand will even out, rendering few arbitrage opportunities. If you rightly assume resources are pretty fairly allocated, then you don’t have to worry about finding the optimization point because it’s already there. This is also known as Pareto Optimal or Pareto Efficiency, where changing one variable changes one or more other variables to where in aggregate the change isn’t worth it.

Enough theory, let’s put this into practice. In practice, I am facing this with moving. I believed I could find a Pareto efficiency better than my current living situation, but the trade-offs slap me in the face every which way as I search for the brighter and better.

Want to be closer to the beach? More expensive.

Want to be in a nice place and close to the beach? Too expensive or too far away from the main city attractions.

Want to be close to the beach but not expensive? Have fun living in a shoebox and/or noise polluted area.

It never ends.

The key realization is knowing the world has already factored in all these variables for you and is priced accordingly. Your job is to get clear on your values. That’s where the real arbitrage happens when you value something enough to justify forfeiting other attributes. Another option is to make so much money that you can have it all, but then your trade-off is slaving away your youth and time to get to a place where you can enjoy your youth and time.

As an optimizer who has banged his head against this wall one too many times, I’m slowly learning to simply appreciate what I have. Why are life’s answers so simple yet so elusive? Tony Robbins talks about humans craving both Uncertainty and Certainty, and that tension is exacerbated by optimizing-prone personality types.

Anyway, that’s all I have to say for now. I’m off to go find something better to do.

“If you have roughly 40% of the information available, continue seeking more information until you get closer to 70%. Once you attain 70% of the information to be had, make the decision!”

Well said! I will incorporate this rule into my daily life decisions.

This one is huge! Something I wish I knew a lot earlier in life so I could spend less time second-guessing and more time moving forward without trepidation. Understanding that perfect information is either impossible and/or unpractical has life-changing implications.